You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Asian films’ category.

Director: Osamu Tezuka

Release date: November 1962

Rating: ★★★

Review:

‘Tales of a Street Corner’ was Osamu Tezuka’s first animated film, and the first production of his company Mushi productions, which Tezuka founded in 1961, after his contract ended at Toei Animations, Japan’s most important animation studio of that time.

The film immediately shows Tezuka’s high ambitions. First, ‘Tales of a Street Corner’ is of considerable length, clocking 39 minutes. Second, its designs echo the cartoon modern style of Europe, unlike anything previous in Japan. Third, Tezuka’s storytelling is highly poetical, reminiscent of Paul Grimault, avoiding tried story cliches. Fourth, the film has a strong anti-militaristic and pacificist tone, and is more than just mere entertainment.

It’s striking to note that, unlike Tezuka’s Astro Boy television series from a year later, ‘Tales of a Street Corner’ lacks any Japanese character. Instead, the film feels very European, both in its looks and in its music. Even the town in which the story takes place is clearly European, as are the poster violinist and pianist. These two characters form the heart of a romantic tale that Tezuka spins, with other protagonists being a little mouse, a moth, and even a broken lantern and a tree.

The whole tale is set in motion when a little girl drops her teddy bear in a gutter, but Tezuka’s story is anything but straightforward, and allows for some poetic moments, as well two series of silly gags involving numerous posters. The animation ranges from full animation to zooming into still images, with everything in between, and it is quite possible that Tezuka’s choices in the complexity of animation were motivated not only by its artistic value, but also by cost reduction.

‘Tales of a Street Corner’ is certainly charming, but as would later be more often the case with Tezuka, the director wants too much within one short. In fact, the short is overlong, and it’s unclear what he wanted the resulting film to be: a children’s film? A romance? A comedy? An anti-war statement? Now, the film is all this and thus none of that at the same time. Nevertheless, ‘Tales of a Street Corner’ remains a delight to look at throughout, and with this film Japan surely entered a new phase in animation, even if the film is still copying its European models.

Watch ‘Tales of a Street Corner’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Tales of a Street Corner’ is available on the DVD ‘The Astonishing Work of Tezuka Osamu’

Director: Kitaro Kosaka

Release date: June 11, 2018

Rating: ★★½

Review:

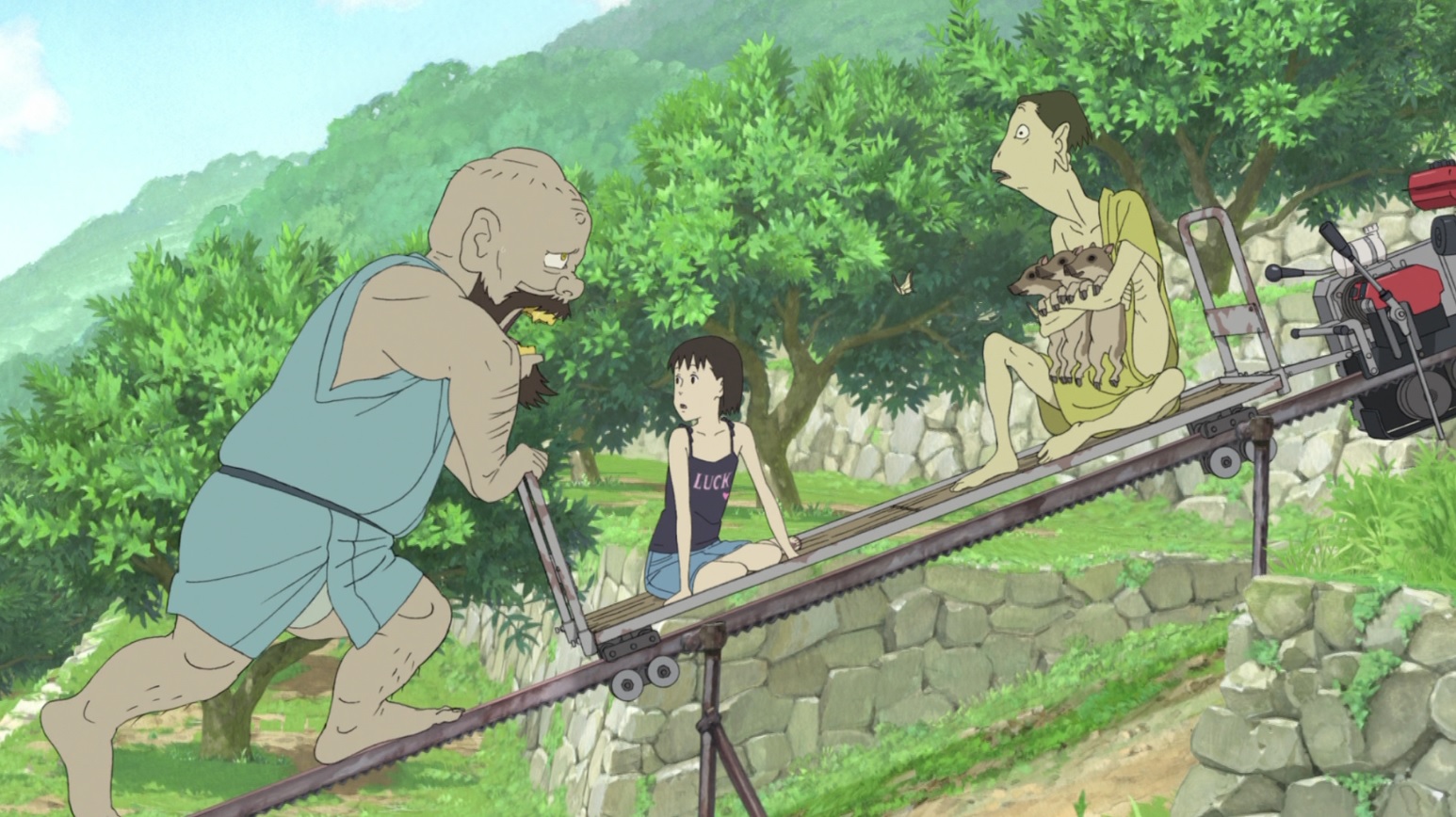

‘Okko’s Inn’ is an animated feature film by Madhouse based on a children’s novel series Hiroko Reijō. The film stars a little girl, who’s still at elementary school when she survives a terrible car accident in which her parents die. After this tragic incident she goes to live with her grandmother, who runs a ryokan, a traditional inn in a spa town near Mount Ikoma, East of Osaka, where she meets some ghost children and even a boyish demon.

Okko is supposed to help at the inn, and naturally we watch her grow into her new life and role, helped by the ghost children and little demon, whom we learn more about on the way, while Okko must deal with a girl whose family runs a larger rival inn.

The movie thus taps from familiar tropes in Japanese animation, like a girl losing her parents, and having to work, and the glories of traditional rural Japan as opposed to modern city life. The movie thus at times is reminiscent of such masterworks as ‘Spirited Away’ (2001) or ‘A Letter to Momo’ (2011). In content that is, for stylistically ‘Okko’s Inn’ is very poor. The designs are the most generic possible, with Okko herself being a particularly standard wide-eyed manga girl, and the animation is only fair. Moreover, the film lacks the subtleties of its peers. The film almost mechanically goes through the motions, as if ticking the necessary boxes, and the narrative lacks the surprising twists and turns of aforementioned examples.

It doesn’t help that the film’s message is partly told through guests of the inn, whose role seems almost to help Okko further in life. There’s a father with a son, whom Okko helps through their grief, and there’s an independent woman, a fortune teller, who befriends Okko and helps her getting more self-confident. And then there’s a third family staying, containing the biggest surprise of all.

The biggest flaw, however, is that we don’t see anything of Okko’s grief at all until the very end of the movie. Most of the time we don’t feel her trauma, we don’t feel her fear and we don’t feel any sense of readjustment. We see some of it, but we don’t feel it: in fact, Okko grows surprisingly easily into her new role. Nevertheless, there’s a scene in which Okko meets her anxieties, and this is by far the emotional highlight of the movie. Unfortunately, this powerful scene is followed by a mindless one on shopping.

‘Okko’s Inn’ is not a bad movie, but it’s not a stand-out either, and the film feels as a poor man’s version of ‘Spirited Away’. If anything, the feature shows that also the Japanese animation industry can pour out films that feel like run-of-the-mill products.

Watch the trailer for ‘Okko’s Inn’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Okko’s Inn’ is available on DVD and Blu-Ray

Director: Eiichi Yamamoto

Release date: September 15, 1970

Rating: ★★½

Review:

The most important development in animation of the late 1960s and 1970s was the coming of animated feature films aimed at adults, instead of children/families. Heralding the new era was George Dunning’s 1968 film ‘Yellow Submarine’, but the two most important film makers pioneering in this new field were Ralph Bakshi in America (with e.g., ‘Fritz the Cat’ from 1972 and ‘Heavy Traffic’ from 1973) and Osamu Tezuka in Japan.

The three adult oriented anime films Tezuka made at his own Mushi Productions studio are called the Animerama trilogy and consist of ‘A Thousand and One Nights’ (1969), ‘Cleopatra’ (1970) and ‘Belladonna of Sadness’ (1973). The three show that Tezuka, like Bakshi, confuses adult oriented with a rather juvenile focus on sex and violence, making the films adult in content indeed, but otherwise rather immature and even exploitative products.

More than its adult orientation, ‘Cleopatra’ stands out for its highly eclectic style. The film tackles a variety of designs and animation styles, none weirder than the opening sequence, which takes place in the future year of 2001, and which starts live action actors with animated faces, an experiment luckily not repeated, for the results are pretty ridiculous, especially because there’s absolutely no lip synchronization, at all.

The film’s plot revolves around an alien planet called Pasatorine, which has a secret plan to wipe out mankind called ‘Cleopatra’. In order to find out the plans a trio of humans, naturally, goes back into time by “psycho-teleportation”, taking the souls of ancient characters in Cleopatra’s time.

Thus, the three main protagonists change identity: Jirov becomes Ionius, a powerful slave, Maria becomes Libya, an Egyptian city girl, and Hal turns into Lupa, a close companion of Cleopatra, who turns out to be a leopard, much to Hal’s chagrin. His character is the most annoying of the film, for the leopard is sex crazed and tries to get laid all the time, despite its animal features.

After ten minutes we’re in Egypt where Tezaku depicts the Roman conquest of the ancient kingdom in a very silly style, accompanied by some attractive space funk music. When we first see Libya, the adult orientation immediately becomes clear, for she’s bare breasted the whole time. The Egyptian plot is bizarre, too, with an ugly freckled girl changing into the sex goddess of Cleopatra with the sole reason to seduce Caesar and to kill him. Adding to the weirdness is the coloring, for Libya is rendered bright red, while Caesar is depicted as a green man.

Stylistically, the film is all over the place, anyhow, altering tiresome silliness and cheap rotoscoping with quite some beautiful graphic imagery, like the stylized fighting of the Romans and the Egyptian conspirators. The animation, too, is a mixed bag, from non-animation and cheating jump takes from pose to pose, without any animation in between, to far more interesting animation done in watercolors. The animation of the horse ride, and the struggle between Ionius and an Egyptian warrior are actually quite good, and even the first two sex scenes are interesting in their semi-abstract and even poetical stylization, while the third is depicted as a broken-down film. At one point the imagery reminds one of UPA or the Zagreb school, and at another point there’s even a cut-out sequence featuring variations on classic paintings.

What the film completely lacks, is character animation. Emotions are just indicated, not felt, and there’s only broad caricature, not character development. The potentially dramatic story is further hampered by random gags, often strange and out of place. Likewise, the story is sloppy and meandering, with the film makers having difficulty on whom to focus. For great chunks of screen time, the three protagonists from the opening sequence aren’t anywhere to be seen, and after the events in ancient Egypt have ended tragically (in that respect the film does follow Cleopatra’s real life), the film ends abruptly, leaving the viewer wondering why the whole ‘psycho-teleportic’ excursion, and thus most of the movie, was needed in the first place.

It must be said: ‘Cleopatra’ is not a good movie. It is more of an experiment than a success, more of a product of its time than a timeless movie, and rather a curio than an essential watch. It is a product of a more experimental era, but after watching the film, one can hardly wonder why this short age of adult oriented experimentalism stopped.

Watch the trailer for ‘Cleopatra’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Cleopatra’ has been released on Blu-Ray

Director: Mamoru Hosoda

Release date: May 16, 2018

Rating: ★★★

Review:

‘Mirai’ was the third feature film Mamoru Hosoda made for his own studio, Studio Chizu. Hosoda favors rather episodic films about growing up, and ‘Mirai’ is no exception, although the film takes place in a much smaller time frame than ‘Wolf Children’ or ‘The Boy and the Beast’.

Main protagonist of the film is ca. four-year-old boy Kun, who lives in a design house in Yokohama (the town is depicted regularly during the film in swooping bird-eye’s view shots), but more importantly, who gets a baby sister, the Mirai from the title. Mirai also means future, and in fact, the Japanese title is ‘Mirai no Mirai’, or ‘Mirai from the future’. Indeed, Kun meets an older version of his younger sister from the future, as well as some other characters, while he struggles to adapt to the new situation he finds himself in.

Because with the coming of little Mirai a lot changes for the young boy: his parents have less attention for him, focusing more on the new baby, they’re more often tired and crabby, and they struggle with combining working and caring, now there are two children around. Needless to say, Kun has a hard time getting adjusted, and even gets jealous of his innocent baby sister.

The film focuses on some key scenes, in which Kun experiences a setback, at least in his own mind, and then something magical happens in the little courtyard of his house. First the little boy first meets a humanized form of the family dog, and then his younger sister in older form (there’s more, but I won’t spoil it here).

Unfortunately, Hosoda doesn’t stick to the boy-sister relationship, and at some point, the magic scenes also help Kun overcome his fears. Moreover, a four-year-old is a difficult and questionable protagonist of a film that wants to show the hero’s progress. After all, he is just a little boy. It’s little surprising that Hosoda spends considerable time on Kun’s parents, and their development during this crucial part of their lives. And, indeed, to be frank, Hosoda’s honest depiction of the hardships of young parenthood and of raising one’s own children is much more interesting than Kun’s ‘development’ of character.

Main attraction of the film are the five magical scenes, with the first two showing some broad comedy, as the man-dog and Mirai from the future roam around the house. The third and fourth start to feel obligatory, even though the fourth has a nice nostalgic feel to it. But with the fifth, Hosoda goes completely overboard, and one wonders why these nightmarish scenes, taking the film to a altogether other atmosphere, were even necessary. In fact, this finale, in which Hosoda wants to tell us something about family ties, is too overtly self-explanatory and spoils a film that wasn’t perfect to start with.

In fact, ‘Mirai’ drags a little, being mostly confined to the small space of Kun’s house and with Kun’s development of character as an important, but very weak story device. The film’s episodic nature doesn’t really help, spreading the story thin, a problem that also invades ‘Wolf Children’ and ‘The Boy and the Beast’. I wish Hosoda was able to keep his use of time as tight as his use of space in this movie. ‘Mirai’ is not a failure, the film is too original for that, but it’s arguably Hosoda’s weakest feature film so far, never reaching the emotional heights of either ‘Wolf Children’, ‘The Boy and the Beast’ or even his debut film, ‘The Girl Who Leapt Through Time’ from 2006.

Watch the trailer for ‘Mirai’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Mirai’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Mari Okada

Release date: February 24, 2018

Rating: ★★★

Review:

The Japanese animation industry apparently is so rich that new interesting films can pop up seemingly out of nowhere. For example, ‘Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms’ (from now on ‘Maquia’) is made by the P.A. Works studio, which since its founding in 2000 focused on television series, and which only made four feature films, the first being based on a video game, the second made for television, the third for training purposes, and the fourth based on a television series.

So, their fifth feature film to be a completely original story, not based on a video game, television series or even a manga, comes as a surprise. It seems that ‘Maquia’ was the pet project by its director Mari Okada, who wrote the story herself. Okada, apparently is somewhat of a modern legend as she has written for over fifty television series since 2001, and is called by Wikipedia “one of the most prolific writers currently working in the anime industry”. She’s one of the brains behind ‘Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day’ (2011), one of only two anime television series I have watched, and it comes to no surprise to me that the ‘Maquia’s’ story style has something in common with that series. Both series and film have a strong focus on human drama, with emotions reigning uncontrolled, and tears flowing frequently. In fact, despite the high fantasy setting, ‘Maquia’ has a strong element of melodrama, and the rather forced emotions, so different from the more restrained style in studio Ghibli, or the films by Yasujirō Ozu for that matter, actually made it harder for me to relate with these people.

‘Maquia’ is a fantasy film, set in a rather Middle Earth-like world, and starts with the depiction of a society of near-immortals called Lorphs, whose surroundings are particularly like the depictions of elven kingdoms in Peter Jackson’s adaptation of The Lord of the Rings. These Lorphs write their memories by weaving cloths and live far away from more mortal men. One of these, a young girl called Maquia (from which the English film title takes its name) rather out of nowhere complaints she is so alone. Shortly after this scene of distress the eternal city is attacked by an army of men, and Maquia soon finds herself in the outside world, where she adopts a baby, whose mother is killed.

From then on, the film takes an episodic nature, showing us various stages of the mother-son relationship until the son, whom Maquia calls Ariel, has matured, while his mother, in contrast, has retained the same teen appearance she had in the beginning.

The film apparently tries to say something about how to love is to lose and to let go, how to find beauty in the short lives we have, and how relationships form the most important part of life, but the film’s messages get deluded in a rather complex story, in which we do not only follow Maquia, but also her childhood friend Leilia, who is forced to become a queen by her abductors, the captain who destroyed the Lorph city in the first place and one Lang, a boy/man with whom Maquia spent her first years in the mortal world. The bigger story, and all its subplots are far less interesting than Maquia’s relationship to her adopted son, and both prolong and distract the film unnecessarily.

Apart from being unfocused and very, very emotional, ‘Maquia’ is also hampered by an overblown score by Kenji Kawai, all too forcefully guiding the viewer in which emotion to feel. Even worse, are the rather lazy and utterly generic human designs, which nowhere transcend your average anime television series. The animation, too, is fair, but not outstanding. There’s also a small dose of computer animation that is used sparingly and effectively. No, the film’s highlights are not the story, music, character designs or the animation, but the background art and the lighting, which are both no less than magnificent, and which both give ‘Maquia’ a splendor that make the film a delight to watch, even when the characters and events themselves don’t.

I like ‘Maquia’ being an original story, and its theme of what it means to be (im)mortal is interesting, but the film is too long, too episodic, too meandering and too dramatic to entertain, and I am pretty sure in the end I will not remember either the film’s story or its characters, but the beautiful background art and superb lighting, which the make the film a standout, after all.

Watch the trailer for ‘Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms’ is avaiable on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Eiichi Yamamoto

Airing date: June 27, 1973

Rating: ★★★½

Review:

The late sixties and early seventies saw some striking experiments in the animated feature film. These films left the tried paths of family film and aimed at a more adult audience. In Europe Walerian Borowczyk arguably made the first experimental animated feature with ‘Théâtre de Monsieur & Madame Kabal (Theatre of Mr & Mrs Kabal)’ (1967), René Laloux made quite an impact with ‘La planète sauvage’ (1973), while in the UK George Dunning’s ‘Yellow Submarine’ (1968) caused a revolution, inspiring for example ‘János Vitéz’ (Johnny Corncob) in Hungary. Meanwhile in the US Ralph Bakshi experimented with more adult themes in ‘Fritz the Cat’ (1972) and ‘Heavy Traffic’ (1973).

In Japan, Osamu Tezuka led the way with his Mushi Productions studio, releasing three more adult themed feature films: first ‘A Thousand and One Nights’ in 1969, followed by ‘Cleopatra’ (1970) and ‘Belladonna of Sadness’ from 1973.

All three were directed by Eiichi Yamamoto, but in contrast to the earlier two features Tezuka had no direct involvement in ‘Belladonna of Sadness’. Even more striking, the great master left his own studio halfway production. Thus, ‘Belladonna of Sadness’ is very, very different from Tezuka’s own rather cartoony creations.

According to Yamamoto he wanted his film to be a Japanese answer to ‘Yellow Submarine’, and to make it one the drew inspiration from the artwork by Kuni Fukai. However, Kunai’s dark and disturbing artwork is quite the opposite from Dunning’s cheerful fantasies. On the Blu-ray Fukai calls his own work from the early seventies ‘decadent’, and that certainly is an apt description. Fukai’s drawings are baroque, graphical, lush, and highly erotic. They have a distinct neo-art-nouveau character, which is both very psychedelic and very seventies. For Belladonna of Sadness’ Fukai functioned as the art director, and his drawings form the base of the complete film, which uses animation only sparingly, often leaving the camera tracking over the static artwork.

And what artwork! ‘Belladonna of Sadness’ sure is a marvel to look at. The watercolor-and-pen drawings are all interesting and of a high artistic quality. Fukai almost always uses a white canvas, in which the drawings more or less disappear, and there’s ample and expressive ornamentation to accentuate the feeling of the scene. There are some odd design choices, however. For example, the villain looks like he has no eyes and as if three bones are stuck into his skull, making him rather grotesque and unbelievable.

Animation, as said, is only used only sparingly. There is no lip-synchronization, whatsoever, and some of the animation is crude and simple. The most interesting animation occurs when the events are not shown directly, but only suggested. For example, in the best erotic scenes more is hinted at than shown, and when the world is struck with the plague, we watch the landscape melt. There are certainly some trippy scenes, full of metamorphosis, which form the best parts of the movie. The undisputed highlight of the film comes when the baroque images are suddenly changed for a rapid-fire delivery of much more cartoony designs in bold seventies colors. This frenzy of animated images is followed by beautiful glass painted animation full of metamorphosis.

The psychedelic images are further enhanced by the soundtrack, which mixes psychedelica, spacefunk and rock into a very seventies-like mix, akin to Alain Goraguer’s soundtrack for ‘La planète sauvage’ from the same year, albeit of a lesser quality. There are even a few songs to enhance the mood.

In contrast to the beautiful art the story of ‘Belladonna of Sadness’ is subpar, and even objectionable. The film is based on ‘La sorcière’ (1862) by Jules Michelet, a non-fiction book on witchcraft, and the film’s story is set in a fictive oppressive kingdom in which a peasant girl becomes a witch. However, Yamamoto’s and Yoshiyuki Fukuda’s screenplay apparently only uses the book as a source of inspiration, as their own tale is as predictable as it is boring.

Yamamoto apparently instructed Fukai that his film was ‘porn but make it a love story’. Well, the movie is certainly porn, but hardly a love story. The two lovers Jean and Jeanne are more vignettes than characters, and if anything, Jean is a weak and will-less coward. Worse, the porn is exploitive, featuring several rapes and a lot of violence. As can be expected, there is a lot of female nudity, but hardly any male one, although penises are omnipresent, especially as the devil takes the shape of a penis himself. Jeanne’s best moment comes when she reveals herself as a full-blown witch, which provides one of the film’s most iconic moments. But during most of the film she’s used and abused by powers beyond her control. The ending, too, is unsatisfying, and all too abrupt, forcingly trying to make the porn story into something political.

Thus, ‘Belladonna of Sadness’ may transcend normal porn (it’s certainly weird and original enough to do so), but not that of a cheap comic. There’s no depth to the story, at all, and the film’s exploitive character gives a bad taste in the mouth. Nevertheless, the movie is a feast of the eye and stands as a great example of the sheer experimentation that were the seventies.

Watch the trailer for ‘Belladonna of Sadness’ yourself yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Belladonna of Sadness’ has been released on Blu-Ray, but this is currently out of print

Director: Hiromasa Yonebayashi

Release date: July 8, 2017

Rating: ★★★½

Review:

‘Mary and the Witch’s Flower’ is the first film by Studio Ponoc, founded by Yoshiaki Nishimura, who was a producer for Studio Ghibli before. Director Hiromasa Yonebayashi, too, is a Studio Ghibli alumnus, being an animator for the famed studio since 1997, and directing the studio’s 21st feature film ‘When Marnie Was There’ (2014).

It comes to no surprise then that ‘Mary and the Witch’s Flower’ is very, very Ghibli-like. Already the packaging of the DVD would fool anyone. But the similarity doesn’t stop there: even the opening titles emulate Ghibli; the character designs, too, are very Ghibli-like; the film is based on a British children’s book, just like Ghibli’s ‘Howl’s Moving Castle’ (2004), ‘Arrietty’ (2010) and ‘When Marnie Was There’; the film stars a young female protagonist (Mary) who has to survive without her parents, just like ‘Kiki’s Delivery Service’ (1997), ‘Spirited Away’ (2001) and ‘From Up on Poppy Hill’ (2010); Mary is a witch like Kiki; she’s accompanied by a cat who plays an important part just like Kiki and like Shizuku in ‘Whisper of the Heart’ (1995), and the film is partly set in a fantasy world, just like ‘Spirited Away’.

Now, this is immediately the film’s main flaw: studio Ponoc imitates Ghibli very well but doesn’t bring anything original of its own. The final product is practically indistinguishable from the source of inspiration. That doesn’t mean, however, that ‘Mary and the Witch’s Flower’ is a bad movie. The story is told well enough, the animation is top notch, and the fantasy world looks great. I certainly had a good time watching it, and would recommend the movie to all lovers of the Studio Ghibli product. But Studio Ponoc’s debut could and should have been something much more of their own. If you compare, for example, ‘Mary and the Witch’s Flower’ to the idiosyncratic ‘Night Is Short, Walk on Girl’ from the same year, it becomes clear which studio brings something original to the world, and which one does not.

Watch the trailer for ‘Mary and the Witch’s Flower’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Mary and the Witch’s Flower’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Masaaki Yuasa

Release date: April 7, 2017

Rating: ★★★★★

Review:

Japan knows several distinguished animation directors, from Hayao Miyazaki to Mamoru Hosoda, but perhaps no feature director* is so original as Masaaki Yuasa. He created quite a stir with ‘Mind Game’ (2004) and kept on pouring out original work since then.

What’s striking about Yuasa’s films is that they don’t follow the general anime aesthetic, at all, on the contrary. ‘Night Is Short, Walk on’ is an excellent example in that respect. This mind-blowing feature film boasts human designs that are very different from your typical anime, highly original color schemes, more offbeat background art, interludes in a line-less style with vibrant digital coloring, wild, even grotesque animation (for example, watch people swallow in the first scene), and a highly original, almost stream-of-consciousness-like way of storytelling, using unpredictable editing techniques, and an occasional split screen, surprising camera angles, extreme perspectives, and moving background art, when necessary (there’s a very impressive example when Senpai runs up an exterior staircase).

Apart from Yuasa’s way of storytelling the plot of ‘Night Is Short, Walk on’ is highly original in its own right. The two main protagonists don’t even have names but are referred to as Otome (maiden) and Senpa (senior). We follow the two for one night, a night in which apparently anything can happen. Otome, a young woman, is ready to discover the adult world, while Senpa, who’s madly in love with her, has decided to finally express his feelings to her. Meanwhile, during this one night, both people meet a plethora of strange people, bizarre situations, and odd gatherings in a free-flowing narrative that nevertheless can be cut into four parts, which naturally flow into each other. Nevertheless, it’s best not to know anything about the plot, and just let it come to you. You’ll be in for quite a ride. What’s more, despite all its weirdness, ‘Night Is Short, Walk on Girl’ is essentially a film about love, and unexpectedly gentle despite all the mayhem surrounding the main story.

Surprisingly for such a visually stunning film, ‘Night Is Short, Walk on Girl’ is based on a novel, by Tomihiko Morimi. His novel was divided into four seasons, which explains the high number of events in the film version. Morimi was also responsible for the novel on which Yuasa’s earlier series ‘The Tatami Galaxy’ (2010) was based, and the series and ‘Night Is Short, Walk on Girl’ are very similar in visual style and general atmosphere.

In all ‘Night Is Short, Walk on Girl’ is hardly like anything you’ve seen before, and a great testimony of what can be done in animation. In my opinion this is one of the most important animation films of the decade. Highly recommended.

* There are also several highly original independent Japanese directors of shorts, e.g. Kōji Yamamura, Atsushi Wara & Mirai Mizue. Check them out!

Watch the trailer for ‘Night Is Short, Walk on Girl’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Night Is Short, Walk on Girl’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Hiroyuki Okiura

Release date: September 10, 2011

Rating: ★★★★★

Review:

To me the Japanese Production I.G. studio is a company hard to grasp what it’s about. Since 1987 the studio produces television series, OVAs, feature films, video games and even music. With its vast production quantity seems more important than quality, and production more important than vision or style. For example, of its fifty plus feature films only a very few created a stir in the West, and these are as diverse as ‘Ghost in the Shell’ (1995), ‘Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade’ (2000), ‘Giovanni’s Island’ (2014) and ‘Miss Hokusai’ (2015).

Of all these ‘A Letter to Momo’ comes closest to an author film. The film was conceived, written and directed by Hiroyuki Okiura, after he had directed the widely acclaimed ‘Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade’. The whole film took a staggering seven years to make, but the amount of work visibly pays off, because ‘A Letter to Momo’ can be placed among the best films ever to come out of Japan, being on the same level as the best from Ghibli, Momaru Hosoda or Makoto Shinkai. It’s therefore highly incomprehensible that the film remains Okiura’s only own creation.

‘A Letter to Momo’ takes place in one hot summer on the island, and tells about Momo, an eleven year old girl whose father has unexpectedly died, and who moves with her mother Ikuko from buzzling Tokyo to the place of her mother’s roots: a quiet rural town on the remote Osaki Shimojima island, somewhere Southeast of Hiroshima in the Seto inland sea. Both events are clearly traumatic experiences to the young teenager, who remains shy, stubborn, withdrawn, and taciturn, despite her mother’s efforts to befriend her with the local children, who surely are willing enough to let her join their group. These early scenes are shown on a leisurely speed, depicting Momo’s boredom, isolation, and loneliness very well.

But things get worse, Momo’s new home turns out to be haunted: there are voices in the attic, and some vague creature seems to follow her mom when she’s off to work. Soon, a trio of goblins manifest themselves to the young girl, and she has a hard time getting used to their presence. During the movie she must learn to live with them, and she finally figures out why they are there in the first place.

The fantasy sequences with the three dimwitted goblins are fun, but throughout the movie Momo’s emotions remain central to the story, especially the loss Momo experiences after her father’s death, her relationship with her mother, who’s also grief-stricken, and her slow opening to the island children. A recurring metaphor of Momo’s transition from being shy, miserable, and scared to a teenager capable of enjoying life once again is shown in a few swimming scenes, in which the island children jump from a high bridge into the sea.

The human drama and the fantasy finally come together in a breathtaking finale when a typhoon visits the island. This sequence is the most Ghibli-like of the whole film. This is the dramatic highlight of a film that otherwise remains modest in how it tells its sweet and moving tale.

The looks of ‘A Letter to Momo’ are no less than gorgeous. The film boasts a rather unique style, with a very high level of realism. The drawings are exceptional for their surprisingly attractive and very thin line work, and the animation, supervised by Masashi Ando, is no less than excellent. Especially, the command of the human form is breathtaking. It apparently took four years to animate the complete film, but every animation drawing of Momo and her mother is a beauty to look at, and absolutely conveys a wide range of emotions and expressions, rarely resorting to anime cliches, if ever. For example, it’s startling to watch someone cough as realistically as Ikuko does in this film. ‘A Letter to Momo’ is also one of those rare Japanese animation film in which the characters actually do look Japanese, with black hair, porcelain to yellow-brown skins and eyes of more realistic proportions than usually encountered in anime.

The background art, supervised by Hiroshi Ôno (who previously worked on ‘Kiki’s Delivery Service’) is gorgeous, too. It does not deviate from artwork of other Japanese animation films, but again, its level of realism is staggering. The documentary on the Blu-Ray I have of this film shows pictures of the real thing, and the film makers have captured the island of Osaki Shimojima astonishingly well. Moreover, they’ve managed to do so, while keeping the background paintings very attractive and always in service of the animated action. There’s a small dose of computer animation, which always remains modest and functional (a boat, a fan, some moving background art), and which doesn’t disrupt the graphic quality of the film.

In all, ‘A Letter to Momo’ is a heart-warming tale on loss and grief, very well made and one of the most gorgeous animation films to come out of Japan to look at. Highly recommended.

Watch the trailer for ‘A Letter to Momo’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘A Letter to Momo’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Koji Yamamura

Release date: September 17, 2011

Rating: ★★★

Review:

‘Muybridge’s Strings’ is Koji Yamamura’s ode to the great Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), pioneer of recording of movement and (thus) of cinema.

Yamamura adopts different techniques to tell his tale, using pencils, pens, and paint to a mesmerizing effect. His film style is surreal, non-linear and associative, and very hard to follow indeed. I’ve learned from this film that Muybridge shot his wife’s lover, but there also images of a woman and a child, often with heads as clocks, which are more difficult to decipher. I guess Yamamura wants to say something on the passing of time, but then the connection to Muybridge is loose and vague. Nevertheless, the film is a marvel to look at, and the sound design, too, is superb.

Watch an excerpt from ‘Muybridge’s Strings’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Muybridge’s Strings’ is available on the The Animation Show of Shows Box Set 9

Director: Gorō Miyazaki

Release date: July 17, 2011

Rating: ★★★★

Review:

Like ‘Ocean Waves’ (1993) and ‘Whisper of the Heart‘ (1995) ‘From Up on Poppy Hill’ is one of those Ghibli films that could do well without animation. There’s no fantasy or metamorphosis around. Instead, the film is a modest little human drama. In fact, the film has much in common with the two earlier Ghibli features. Like ‘Whisper of the Heart’ ‘From Upon Poppy Hill’ has a female teenager star, and like ‘Ocean Waves’ there’s a strong air of nostalgia pervading the movie, especially in the gorgeous and evocative background art.

‘From Upon Poppy Hill’ takes place in harbor town Yokohama, somewhere between 1961 and 1963, before the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo and after the release of the melancholic song ‘I Look Up as I Walk’ by Japanese crooner Kyu Sakamoto, which is heard several times during the movie, and which even became famous in the West back then, with the silly and out-of-place title ‘the Sukiyaki song’.

‘From Upon Poppy Hill’ focuses on teenager Umi Matsuzaki who lives with her grandmother and little brother at a boarding house with five female boarders, for whom Umi cooks breakfast and dinner. Umi’s mother is a professor, who’s abroad most of the time, while her father, a seafarer, has died in the Korean war (1950-1953). Each day Umi raises some signal flags in remembrance of her father. These are seen by Shun Kazama, a schoolmate who works at a tugboat. Both Umi and Shun thus are hard working children, so typical for the Ghibli studio.

The story focuses on the love that grows between Umi and Shun, and some unforeseen complications it raises. But there’s also an important subplot in which Shun and his fellow students try to protect their old club house called ‘The Latin Quarter’ against demolishing. Only when Umi starts to help, leading an army of female students, the protest gains momentum. The clubhouse scenes provide some comic relief in an otherwise emotional deep and heart-breaking story of friendship, love, and loss.

It’s impressive how the film makers show the emotions in the subtlest of ways. For example, at one point Shun evades Umi’s presence, but we see her reaction to this neglect only sparingly on her face, and with the slightest of actions. Thus, when Umi finally lets her emotions flow, it hits the viewer all the harder.

Hayao Miyazaki’s son Gorō Miyazaki does an excellent job as a director, and the animation is top notch, especially on the main characters. There are a few flashback scenes and there’s a short dream sequence, but otherwise there’s a strong unity of time and place, with all the action taking place in only a few settings and in a limited time frame. The film thus stays focused all the time, even when showing minor deviations from the main plot, like one of the boarders leaving the house.

In all, ‘From Upon Poppy Hill’ may be a modest film, in its emotional depth it’s in no way less impressive than the studio’s more outlandish masterpieces like ‘Spirited Away’ (2001) or ‘Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea’ (2008). Highly recommended.

Watch the trailer for ‘From Up on Poppy Hill’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘From Up on Poppy Hill’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Eric Khoo

Release Date: May 17, 2011

Rating: ★★★

Review:

The film ‘Tatsumi’ celebrates the work of Japanese manga artist Yoshihiro Tatsumi (1935-2015). Tatsumi is the inventor of the gegika manga style, a grittier, more alternative form of manga for adults. The film re-tells five of Tatsumi’s short stories in this this style, all from 1970-1972. These stories are bridged by excerpts from his drawn autobiography ‘A Drifting Life’ from 2008.

Thus, the film is completely drawn (only in the end we see the real Yoshihiro Tatsumi), but to keep the manga style intact the film was animated with Toon Boom Software, specialized in ‘animatics’, which brings story boards to life. Thus, full animation, although present, is rare, and most of the motion is rather basic, often lacking any realism of movement. The animation is enhanced by limited digital effects, and the first and last story are digitally manipulated to make the images look older.

The complete film thus is little more than slightly enhanced comic strips. One wonders if this is the best way to present Tatsumi’s work, as most probably his stories work better in their original manga form, but of course the movie is a great introduction to his work, which without doubt is fascinating and original.

Tatsumi’s manga style clearly deviates from his example, the great Osamu Tezaku. Tatsumi’s style is more raw, sketchier and knows nothing of the big eyes so common in manga. All but one story use a voice over narrator. And all but one are in the first person. The stories themselves are gritty, dark, depressing and bleak. The second story, ‘Beloved Monkey’, in which a factory worker falls in love with a girl at a zoo, is particularly bitter. The outer two take place just after the end of World War II and show the effects of Japan’s traumatic loss. All are about the losers in life, struggling at the bottom of society. As Tatsumi himself says near the end of the movie:

“The Japanese economy grew at a rapid pace. Part of the Japanese population enjoyed the new prosperity. The people had a great time. I couldn’t bear to watch it. I did not share in the wealth, and neither did the common people around me. My anger at this condition accumulated within me into a menacing black mass that I vomited into my stories.”

Surprisingly, the protagonists of all first-person stories, including the autobiography, all look more or less the same, as if Tatsumi couldn’t create more than one type of hero. Only the third story, ‘Just a Man’, the only one to use a third person narrator, stars a different and older man, while the last story, the utterly depressing ‘Good-bye’, is the only one to have a female protagonist. Tatsumi’s own life story is told in full color which contrasts with his short stories, which are mostly in black and white. Tatsumi’s autobiography is less compelling than his story work but adds to the understanding of the artist and his work.

Surprisingly, for such a Japanese film ‘Tatsumi’ was made in Singapore and animated in Indonesia. According to Wikipedia Singaporean director Eric Khoo was first introduced to the works of Yoshihiro Tatsumi during his military service, and immediately was stricken by his stories. When ‘A Drifting Life’ was published in Singapore in 2009, Khoo realized that Tatsumi still was alive and wanted to pay tribute to him. Tatsumi himself was greatly involved in the film and narrates his own life story. The movie is a great tribute to one of the more original voices in Japanese manga, and well worth watching, if you can tolerate a dose of sex and violence.

Watch the trailer for ‘Tatsumi’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Tatsumi’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Makoto Shinkai

Release date: May 7, 2011

Rating: ★★★

Review:

After the intimate and realistic ‘5 Centimeters per Second’ (2007) director Makoto Shinkai embarked on an ambitious, long and way more fantastical project, which is ‘Children Who Chase Lost Voices’. The film remains an oddball inside Shinkai’s oeuvre and shows a huge Ghibli-influence absent from his other films.

The film starts realistically enough, with little schoolgirl Asuna exploring some gorgeous nature at the other side of a railway bridge and visiting a secret hideout there. But the fantasy immediately kicks in when she brings forth a strange radio-like apparatus based on some sort of crystal. The use of this device triggers a series of events that eventually leads her to no less than the boundary between life and the afterlife.

‘Children Who Chase Lost Voices’ knows high production values. Like ‘5 Centimeters per Second’ the background art is no less than stunning to begin with, especially the views of and from Asuna’s hill are gorgeous pieces of mood and light. Other scenes are perfect renderings of a hot summer. And like in the previous films, some of these intricate background paintings are only visible for a few frames. Typically for Japanese films some shots are just short mood pieces, in this film surprisingly often depicting insects, like dragonflies and cicadas.

The animation, too, is excellent, as is the shading on the characters themselves. The character design, on the other hand, is less original, and remarkably reminiscent of Miyazaki’s and Takahata’s work at the Toei Studios during the 1970s.

But this is only one of the obvious Ghibli-influences. Asuna herself is almost a typical Miyazaki-heroin: living without a father and a largely absent mother she’s depicted cooking and caring for herself and doing all the household work. She’s thus one of those working children that crowd the old master’s films. She’s joined by a cat called Mimi, which immediately brings Jiji to mind from ‘Kiki’s Delivery Service’ (1989). There’s a villain that echoes colonel Muska from ‘Laputa: Castle in the Sky’ (1986), and there are some God-animal hybrids seemingly coming straight out of ‘Princess Mononoke’ (1997).

Shinkai absolutely succeeds in painting Asuna’s world. It’s a pity that most of the film takes place in Agartha, a mythical place underground the design of which is less compelling and even disappointing. When compared to the fantastical works of Ghibli’s ‘Laputa: The Castle in the Sky’, ‘Princess Mononoke’ or ‘Spirited Away’ (2001) Shinkai’s worldbuilding clearly is subpar. For example, this subterranean world knows blue skies, sunlight, clouds, and rain, which all go unexplained. Apparently, there are no stars, but that’s about it. The underworld characters live in some quasi-medieval society, but this too, is hardly worked out or explained to the viewer. Shinkai’s erratic handling of the underworld seriously harms its believability. After all, it’s hardly different from ours, and both its reason of existence and its purpose remain vague and undecided.

It doesn’t help that Asuna explores this world with one Mr. Morisaki, who is a member of some secret society, but who descends into the earth to retrieve his deceased wife. Both Morisaki’s background story and introduction make frustratingly little sense. For example, there’s a flashback which seems to indicate he was alive during world war I, and for no apparent reason and with little likelihood he poses as Asuna’s substitute teacher. The secret society is utterly unnecessary to the plot, which is too complex for its own good. Moreover, Morisaki remains a vague and unconvincing character getting much too much screen time, and he never turns into either the scary villain Muska was in ‘Laputa: The Castle in the Sky’ or one of those cleverly ambivalent antagonists of Miyazaki’s other films.

In fact, the scenes in Agartha start to drag, and the film loses focus, when leaving Asuna to concentrate on one of the underworld’s inmates, a boy called Shin. In the end Asuna is an all too will-less pawn in Morisaki’s scheme and she lacks her own clear story arc. This is in fact the film’s core problem: this should be Asuna’s story, but the film loses her halfway. It doesn’t help that Asuna’s own relationship to her deceased father is hardly developed, if at all. Particularly puzzling is a scene in which Asuna suddenly utters that Morisaki is like her father. Now where did that come from?!

The roles of Shin and the mute Manna remain vague, too, and feel half-baked. For example, Manna is abandoned halfway the film not to return. Instead, they add to the complexity of the story, further obscuring Asuna’s story arc. During the finale, in which Morisaki finally meets God (!) and Asuna is even depicted in the afterlife (!!) the last traces of believability go out of the window. Compare this rather blunt and all too direct storytelling with the Orpheus myth itself, which is clearly one of its inspirational sources, and one regrets Shinkai didn’t go for much more mystery.

The aftermath, in which our protagonists wander all the way back home is even worse, done in a short montage the story deflates over the end titles, accompanied by a cheesy song. This is a disappointing ending of an overlong and poorly timed film, indeed. Add some unnecessary gore, a plethora of unresolved story lines, three all too forced explanation scenes, and one can only conclude that Shinkai utterly fails where Miyazaki succeeds.

Luckily, ‘Childern Who Chase Lost Voices’ remained a one-time experiment. With his next film, ‘The Garden of Words’ Shinkai returned to much more familiar terrain, with far better results.

Watch the trailer for ‘Children Who Chase Lost Voices’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Children Who Chase Lost Voices’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Tatsuyuki Nagai

Airing of first episode: April 14, 2011

Rating: ★★★½

Review:

After ‘Erased‘ this is only the second Japanese anime series I’ve seen. The two series are from the same A-1 Pictures studio, and they are about of the same quality, so how they compare to others I wouldn’t know. Like ‘Erased’ ‘Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day’ deals with friendship and loss, this time featuring on a group of six high school friends.

In the first of eleven episodes we learn that Teenager boy Jintan, who has dropped out of school, is troubled by a childish blonde girl called Menma, but it turns out he’s the only one seeing her. Soon we learn that Menma is dead, and that she was part of a group of friends led by Jintan when they were kids. After her death the group fell apart, but Menma is back to fulfill her wish. Unfortunately, she herself doesn’t know anymore what her wish was…

Menma’s unknown wish is the motor of the series, as the friends slowly and partly reluctantly regroup as they are all needed to fullfil Menma’s wish. On the way we learn that each of them had a particular relationship to either Jintan or Menma, and they all have their own view on the day of Menma’s fatal death. And what’s more, there are more traumas to overcome.

‘Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day’ is surprisingly similar to the later ‘Erased’: there’s a jumping from the now to the past (although in Anohana these are flashbacks, not real jumps through time), there’s a supernatural element, there’s a group of friends, and one important mysterious girl who’s dead.

The first episode contains enough mystery to set the series in motion, but the show progresses painfully slowly, and at times I got the feeling Mari Okada’s screenplay was stretched over too many episodes. Especially episode five and six are of a frustratingly static character. In these episodes Jintan, the main character, is particularly and annoyingly passive, hardly taking any action to help Menma or himself, while Menma’s continuous cooing sounds get on the nerve.

The mystery surely unravels stunningly slowly in this series, and only episode seven ends with a real cliffhanger. Even worse, there are some serious plot holes, hampering the suspension of disbelief. Most satisfying are episode eight and ten, which are both emotional, painful, and moving. In contrast, the final episode is rather overblowing, with tears flowing like waterfalls. In fact, the episode barely balances on the verge of pathos. To be sure, such pathos occurs regularly throughout the series. In addition, there are a lot of unfinished sentences, startled faces, strange expressions, often unexplained, and all these become some sort of mannerisms.

The show is animated quite well, with intricate, if unassuming background art. Masayoshi Tanaka’s character designs, however, are very generic, with Menma being a walking wide-eyed, long-haired anime cliché. Weirdly, one of Anaru’s friends looks genuinely Asian, with small black eyes, while all main protagonists, with the possible exception for Tsuruko are depicted with different eye and hair colors, making them strangely European despite the obvious Japanese setting. For example, Menma has blue eyes and white hair, while Anaru has hazel eyes and red hair.

In all, if you like an emotional ride, and you have patience enough to watch a stretched story, ‘Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day’ may be something for you. The series certainly has its merits, but an undisputed classic it is not.

Watch the trailer for ‘Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day’ and tell me what you think:

‘Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day’ is available on DVD

Director: Gisaburō Sugii

Release Date: July 7, 2012

Rating: ★

Review:

‘The Life of Budori Gusuko’ is a film adaption of the novel of the same name by Kenji Miyazawa from 1932. Earlier director Gisaburō Sugii had filmed ‘Night on the Galactic Railroad’ (1985) by the same writer. Strangely, in both films, the characters are inexplicably depicted as cats. The reason of this goes completely beyond me, as Sugii does nothing with the idea of the characters being cats. They’re just humans in a cat shape.

I haven’t seen ‘Night on the Galactic Railroad’, yet, but I understand this film is some kind of classic. I wish I could say the same of ‘The life of Budori Gusuko’, but not so. This film is very disappointing in almost every aspect.

The story tells about Budori Gusuko, a blue cat, and the son of a lumberjack somewhere in the mountains. One year summer never comes, and famine comes to the land. Gusuko’s family disappears, and during the film he keeps on looking for his lost younger sister Neri. Starvation and loss presses Gusuko to leave the mountains…

The story takes place in some parallel world, but Sugii’s world building is annoyingly sloppy. The mountains in which Gusuko grows up are unmistakably European in character, but when Gusuko descends into the valley, we suddenly see very Asian rice paddies. Once we’re in the city, the setting becomes some sort of steampunk, with fantastical flying machines, while Gusuko’s second and third dream take place in some undeniably Japanese fantasy world. The volcano team, too, is typically Japanese.

But worse than that is the story itself. The film is frustratingly episodic, with things just happening on the screen, with little mutual relationship or any detectable story arc. A voice over is used much too much, and there are three very long dream sequences that add very little to the story, and the inclusion of which is more irksome than welcome.

The main problem is that Gusuko’s life story is not particularly interesting. The character himself is frustratingly passive and devoid of character. And worse, after the dire straits in the mountains, he hardly suffers any setbacks. Down in the valley he gets help and work immediately from a friendly but rather reckless farmer called Red Beard. Only when bad harvests hit the valley, too, Gusuko is forced to leave him, too, to descend once more to the city.

Likewise, in the city, Gusuko immediately reaches his goal. There’s some vague climate theme, but Gusuko’s proposed solution is questionable to say the least. Because we learn so little about Gusuko’s motives and inner world (the three dream sequences don’t help a bit) Gusuko’s last act comes out of nowhere. Nor do we care, because Gusuko never gained our sympathy in the first place. The resulting film is appallingly boring.

It must be said that ‘The Life of Budori Gusuko’ can boast some lush and outlandish background art, qualitative if unremarkable animation, adequate effect animation, and a modest dose of apt computer animation when depicting moving doors, lamps, factory parts, flying machines and of Gusuko ascending the stairs. There’s even some puppet animation during the second dream scene. Moreover, the sparse chamber music score is pleasant and effective. Composer Ryōta Komatsu makes clever use of strings, harpsichord, accordion, and percussion. But all these positive aspects cannot rescue a film whose central story is a bad choice to start with.

Surprisingly, this was not the first animated adaptation of the novel. In 1994 the Japanese Animal-ya studio had made another adaptation. It puzzles me what the Japanese see in this terribly boring tale with its questionable message.

Watch the trailer for ‘The Life of Budori Gusuko’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘The Life of Budori Gusuko’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Keichii Hara

Release Date: May 9, 2015

Rating: ★★½

Review:

Based on a manga from the mid-1980s by Hinako Sugiura ‘Miss Hokusai’ is one of those rare animation films unquestionably directed to an adult audience. The film celebrates Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and his daughter, fellow artist Katsushika Ōi (ca. 1800-ca. 1866), whose art matches her father’s.

The film is no biopic, however, only spanning a short time, when Ōi is ca. twenty years old. Moreover, the film consists of a multitude of short scenes, mostly seemingly unrelated and hardly building a story. For example, there are two artists romantically interested in Ōi, but this amounts to no romance. Ōi seems vaguely interested in her own sexuality, but also this theme is hardly worked out.

The most substantial story line is that of Ōi’s younger stepsister O-Nao, who is blind, and whom Hokusai refuses to visit. However, there’s no real story arc, and the film fades in and out without much conflict or personal progress. Emotions remain understated throughout, and it’s telling that the film’s most delightful scene involves a boy playing with O-Nao in the snow, a scene in which Ōi hardly takes part.

It doesn’t help that Ōi mostly is a taciturn, frowning, and uninviting character, who rarely smiles. Her father is more colorful, but cold, selfish and equally clammed-up and phlegmatic. Neither of the two is very sympathetic, and the charm of the film lies not particularly with these characters, but with a series of supernatural events related to Hokusai’s art.

The other characters, mostly artists, are too sketchy to be of real interest. To Western viewers Totoya Hokkei, one of Hokusai’s students, is most interesting, for here’s a rare Japanese anime character actually depicted with slit eyes, depicting the epicanthic fold. There’s also a dog, which I guess, is supposed to be some sort of comic relief.

Above all, the film manages to paint a very lively portrait of Edo (19th century Tokyo), especially the busy Nihonbashi bridge, which is rendered beautifully with help of computer animation. This bridge takes a central place in the narrative, and the films starts and ends with it. Hokusai’s famous Great Wave off Kanagawa can also be seen briefly around the 21-minute mark. Computer animation is also used effectively in the scene in which Ōi runs through the nightly streets of Edo.

The traditional animation is fair, but not exceptional, and firmly rooted in Japanese anime traditions. The soundtrack uses very uninteresting modern music and is mostly at odds with the 19th century scenes.

In all, ‘Miss Hokusai’ is too fragmentary, too unfocused, and too bland to entertain. Both Hokusai and Ōi ultimately deserve better.

Watch the trailer for ‘Miss Hokusai’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Miss Hokusai’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director Tomohiko Itō

Airing of first episode: January 8, 2016

Rating: ★★★½

Review:

‘Erased’ (the Japanese title translates as “The Town Where Only I Am Missing”) is an anime miniseries consisting of a mere twelve episodes and telling about young adult Satoru, who’s apparently often transported a few moments back in time to prevent some horrible disaster.

This is a weird concept to start with, especially because it’s never explained nor used consistently during the series. But this is the starting point of the complete series. Anyhow, when a mysterious killer goes rampant, threatening Satoru’s own very existence, he’s suddenly sent back not a few moments back into time, but way back to February 1988, when Satoru was eleven years old. Moreover, Satoru’s transferred to a different place, as well, his childhood hometown of Chiba, near Tokyo.

Satoru, who keeps his adult mind, knows he must do something about his classmate Kayo, a girl who has visible bruises because she’s molested by her mother, but who also is the first victim of a child-abducting serial killer that terrorizes the neighborhood, something Satoru knows beforehand, because he relives the past. He has only a few days to set things right. Will he be able to rescue Kayo and the other children from the clutches of the murderer, this time?

The series thus plays with the wish to go back in time to do things differently than you have had before. Satoru certainly changes the behavior of his eleven-years old self, changing from a rather distant, lonesome child into one who becomes a responsible and valuable friend, discovering the power of friendship along the way.

Now this is the first anime series I’ve seen in its entirety, so to me it’s difficult to assess the series’ value compared to others. In the distant past I’ve seen episodes from ‘Heidi’ (1974), ‘Angie Girl’ (1977-1978), and ‘Candy Candy’ (1975-1979), as well as ‘Battle of the Planet’s (1978-1980), the Americanized version of ‘Gatchaman’, but that’s about it – the only other more recent series I’ve seen is ‘FLCL’ (2000-2001), but I’ve only seen the first couple of episodes, so I cannot judge that series in its entirety.

Nevertheless, ‘Erased’ receives a high rating on IMDb, thus is clearly valued as one of the better series. And I can see why. The series is very good with cliffhangers, and there’s enough suspense to keep you on the edge of your seat most of the time. Moreover, apart from the time travelling and killer plot, there’s a sincere attention to the horrid effects of child abuse. Even better still, the series shows how being open and friendly towards others can make a significant positive change to their lives, as well as to your own. This is a rare and very welcome message, which the series never enforces on the viewer, but shows ‘by example’.

I particularly liked the fact that each episode starts with an intro, which is not an exact recapture of events in the previous episode, but which contains new footage, subtly shedding new light on the events. Nevertheless, ultimately, the thriller plot, which its red herrings, false alarms, and rather unconvincing villain, is less impressive than the subplots on child abuse and friendship.

Indeed, the series’ best parts all play in February-March 1988, not in the present, with the gentle eight episode, ‘Spiral’ forming the series emotional highlight. The creators succeed in giving these school parts an air of nostalgia, as exemplified by the leader of the series, which is intentionally nostalgic, focusing on Satoru’s childhood, before becoming more confused, indicating a lot, without revealing anything. Oddly, the intro is accompanied by neo-alternative guitar rock, suggesting more the early nineties than late 1980s.

Anyhow, when focusing on the relationships between the children the series is at its very best. In fact, I wonder why the creators didn’t make this series without the rather enforced killer plot. In my opinion the series needn’t any, although it certainly accounts for some chilling moments, like when Satoru becomes a victim of child abduction himself…

Unfortunately, the creators of ‘Erased’ are better in building its subplots than ending them. The last three episodes become increasingly unconvincing. They quickly lost me, making me leave the series with a rather sour taste in my mouth. The finale certainly stains the whole series and diminishes its power.

I have difficulties to say something about the design and animation. The animation, typically for television anime, is rather limited, but still looks fine, as does the staging. The character designs and background painting, however, don’t transcend the usual Japanese conventions, and are indeed pretty generic. In that respect, ‘FLCL’, the only other anime series I can say something about, is much more cutting edge.

In all, ‘Erased’ is a gripping series with a very welcome attention to the horrors of child abuse and the benefits of friendship. I’d certainly say it deserves a watch, even if it can turn out a little disappointing one, given the series’ potential.

Watch the trailer for ‘Erased’ and tell me what you think:

‘Erased’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD

Director: Mamoru Hosoda

Release Date: June 25, 2012

Rating: ★★★½

Review:

Director Mamoru Hosoda rose to prominence with the feature films ‘The Girl Who Leapt Through Time’ (2006) and ‘Summer Wars’ (2009), both made at the Madhouse studio.

To make his next film, ‘Wolf Children’ he created his own studio, Chizu, allowing him to make ‘author films’. And indeed, Hosoda has proven to be a strong voice in Japanese animated cinema, especially with ‘The Boy and the Beast’ (2015). Many place ‘Wolf Children’ in the same league, but I’d disagree, as I will explain below.

‘Wolf Children’ tells about Hana, a student who falls in love with an enigmatic boy, who turns out to be half man half wolf. She bears him two children, who have inherited her boyfriend’s dualistic nature, but then he dies, and she must raise the two on her own. But how will she manage as her children are both human and wolf?

The film encompasses a long time period, up to ca. twenty years, and from time to time a voice over (by Hana’s daughter Yuki) takes over. The film thus is very episodic, but also remarkably low key, poetic and tranquil. Several scenes are mood pieces, only carried by music, letting the images do the work. Moreover, most of the emotions are seen from a distance, and the most dramatic moment of the movie, Yuki’s rescue of her little brother Ame, isn’t even shown.

Unfortunately, the episodic nature also means that the film lacks focus. The story doesn’t stay with Hana but diverts to the experiences of Yuki and Ame and back, story lines are introduced and dropped as well as characters. For example, when Hana moves to the countryside, several scenes are devoted to her relationship with the villagers, most importantly one grumpy old Nirasaki. But later this theme is dropped, and the characters are not seen again.

Hosoda does succeed in showing how little events in children’s lives can change their character and outlook on life forever. Indeed, Yuki and Ame go different directions in life, proving that one upbringing can have very different outcomes.

Despite the film’s interesting message, the lack of focus, the episodic nature, the slow speed, and the sheer length (the film clocks almost two hours) all hamper the film. One wishes Hosoda dared to be more concise, killing more darlings.

Moreover, stylistically the film doesn’t deviate from the general anime style. As all other anime films of the era, the movie exploits very realistic and intricate background art, and the character design feels generic and uninspired, despite being designed by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto of ‘Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water’ (1990) and ‘Neon Genesis Evangelion’ (1995) fame. In fact, with their rather ugly line work and flat colors, the characters contrast greatly with the often beautiful background art, and are simply subpar.

The animation and cinematography, on the other hand, are excellent, and there’s some clever use of computer animation, especially during the scene in which Yuki and Ame run through a snow-covered forest.

‘Wolf Children’ is certainly an interesting and by no means a bad movie, but for a director being able to do his own thing, Hosoda certainly could have been more daring artistically, and more focused storywise.

Watch the trailer for ‘Wolf Children’ yourself and tell me what you think:

‘Wolf Children’ is available on Blu-Ray and DVD